Happy Sunday, friends! And Happy Father’s Day to all the dads out there. Today is, of course, a bit of a solemn day for me as I remember my own father and no longer get to share these days with him in person. Ah, the hope of heaven is truly sweet on these days.

Next week, I’m going to share part 2 of studying the Bible, which will focus on how I go deeper with my study time. This week, though, I want to share an essay I wrote for The Storied Outdoors on Father’s Day in 2022. If you’re not familiar with this podcast, the hosts are Bryan Gill and Brad Hill, and they describe it as being “somewhere between Lewis and Tolkien and Lewis and Clark”, highlighting stories that have shaped the lives and faith of outdoorsmen and women. The podcast is available on Apple, Spotify, and other major platforms, and you can follow them on Instagram at @thestoriedoutdoors.

If you want to listen to the essay I’m sharing today, you can check out the link here, or search up episode 50 on any platform.

This essay highlights how my dad’s storytelling shaped my childhood, hardships we faced with his health and how that affected our relationship, how I learned to become a deep listener and revive the storytelling traditions of our youth, and how storytelling ties in our faith and relationships today.

As we jump in, I want to acknowledge that a lot of my stories about my dad and childhood seem perhaps over-romanticized. All I can say to that end is…

You should have been there in person.

Father’s Day 2022

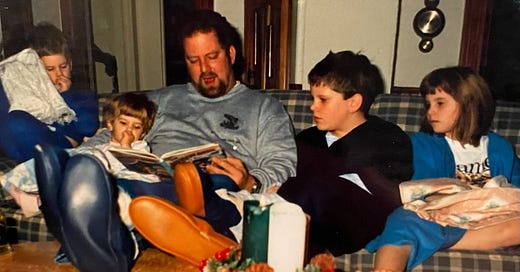

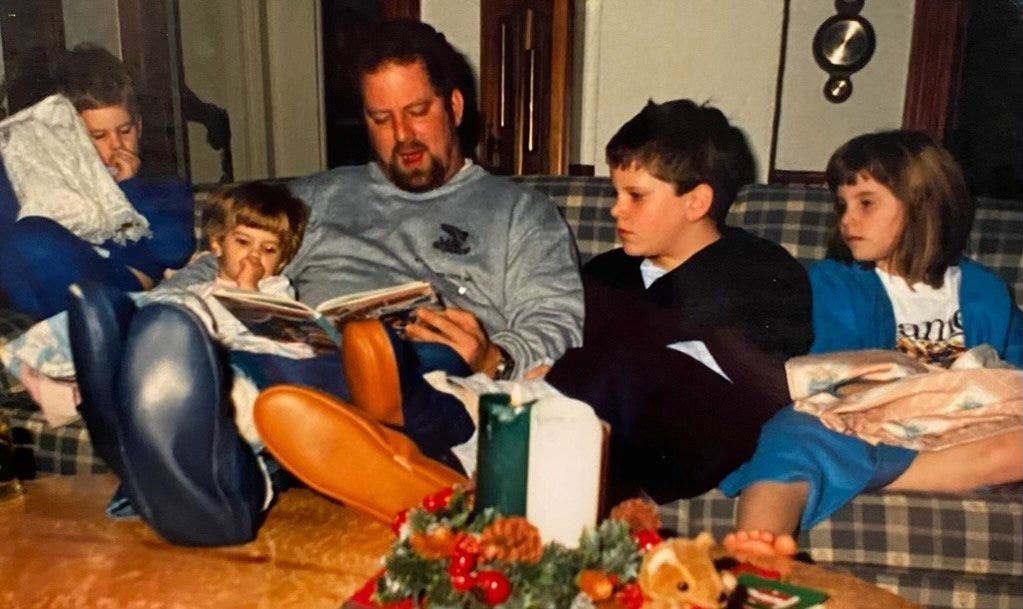

As a child, I loved to hear my father’s stories. He told them with piercing blue eyes, waving hands, and passion as if he was reliving it again. To me, he seemed like a man of the greatest adventures. He had hunted antelope and flown a plane. He had gotten into plenty of trouble in his youth, and he was always traveling and coming back with gifts from wherever he’d been. He had a way of telling stories from his youth growing up in Detroit, visiting grandparents in West Virginia and Iowa, that drew us in and painted a picture of a blonde little boy full of piss and vinegar in all the nostalgic Americana a childhood could possess. Stories like these keep us connected to our origins - where we came from and God’s Hand providentially guiding us to where we came to be.

And our childhood was very much shaped by those stories. There’s an old side-by-side 12 ga. shotgun that hangs over his office door. It’s from his grandfather’s farm in Iowa, where for Christmas one year he received his first BB gun. Gramps had told him he had to wait to shoot it, but my dad had been so excited that he took it upstairs to his bedroom, propped an old pie tin up against his wall, and quietly pumped BBs into that tin. When he was finished, he realized the BBs had gone through the tin and into the wall, so he grabbed a rocking chair and moved it in front of the wall. When his mother came upstairs, she noticed the chair was moved and quickly discovered what he had done. Without saying much to my dad, she left and told her own father - Gramps. Winter in Iowa means grueling cold wind ripping across the Great Plains, but Gramps took this pathetic little boy outside and put his side-by-side 12ga. shotgun in his hands and told him to shoot. My father did, and after he picked himself up off the ground, Gramps told him to fire the other round. What followed was a talk about respect and power - and yes, very layered meanings when we’re talking about grandfathers and guns.

So when it came time for us to start begging for BB guns, the rule in our house was that we had to shoot the 12 ga and get a similar talk. This rite of passage is how we learned that guns had terrifying power, and that they were a tool for hunting, sport, protection, and even some monetary appreciation. (I first shot it when I was eight, and, being the runt of the 4-kid litter, my dad held me up so the kick didn’t blast me over.)

Every experience we had came with a story from Dad, and we absolutely ate them up.

But somewhere between being an eight-year-old tomboy who wished I could be a ninja turtle and becoming a 32-year-old divorcee trying to figure out life, the stories had become fewer and fewer.. As my siblings and I became more involved in school, sports, music, and social lives, our time sitting around the living room talking became more scarce. We still ate dinner as a family every night, but as things go for most American households, things get busier as kids get older, and we outnumbered my parents 2-1. It was always go, go, go.

By the time my siblings had grown and left the house, I was spending most of my time training at the ski resort or off on some backroad cruising around with my friends, drenched in the blissful utopic nonsense of growing up in the northern Michigan summertime. It was exciting, heavenly, independent.

And then it was over. I went to college. I made bad choices. I made good choices. I began to follow Jesus. By the time I finally figured out what I wanted to do with my life, it meant going through my entire Master’s degree in a year and then moving to Colorado. By that time, I was 24, and my father’s health had begun a slow decline. There were hospital stays, doctor’s appointments, and much to worry about from afar. He had quit smoking permanently, but when I moved back to Michigan in 2012, he immediately needed a quadruple bypass surgery, which was scary for the whole family.

For me, the heart surgery began the serious realization that my dad was not, in fact, invincible. I think many of us reach that point with our parents when worry becomes our readiest feeling toward our parents. But it wasn’t just this dynamic in our relationship that had changed. As the years went by, I felt a strain in our relationship that I couldn’t quite figure out. I was getting older, gaining more knowledge and leadership, becoming more of an expert in my field. The urge to lead conversations the way I did in other circles of my life dominated many of my interactions with both of my parents, but I often felt like my dad and I were mutually frustrated with each other by the time we were done talking.

Don’t get me wrong. He was always there for me. He and my mother celebrated my marriage with all their hearts in 2017, and they grieved with me, defended me, and supported me when my husband had a tragic mental breakdown and decided to leave in 2018. He has always been so proud of my accomplishments in my education and career, always one to brag to random strangers about where I live and what I’m doing. I’ve never doubted for a moment that we are truly kindred hearts as the youngest of our siblings - the daring ones, the rogues.

There just seemed to be this disconnect.

In the summer of 2019, I attended a week-long professional development seminar in Colorado. The topic: deep listening. It was a deplorable conference made worse by being trapped within the confines of a boarding school, forced to stare at mountains I could not touch, much less climb. But I remember on the way back to Pittsburgh, I kept thinking I just really needed to call my dad. The last few conversations I’d had with him before the conference had been rough and frustrating for both of us.

But I’ll never forget that I had this epiphany in a Denver airport bathroom on the way home. I finally had a moment to catch my breath amidst a chaotic travel itinerary, and that disconnect was heavy on my heart. So I uttered a little prayer, and it suddenly dawned on me that my relationship with my dad seemed to revolved around two things: his health and my desire to be heard.

Over time, as I delved further into adulthood, my desire to speak and for others to listen had intensified. It was an honest desire. I was eager to prove to my parents and older siblings how much I had grown, matured, become wiser and more knowledgeable. I wanted to speak the Truth of the Gospel over them and teach them more abou the things of God.

Simultaneously, my father’s health had declined over that same time period. I was worried about him, and every conversation became frustrated by that worry. I wanted him to follow the prescribed protocols, change his attitude, change his habits. I wanted to talk to him about Jesus. I wanted to talk to him about his heart. I wanted to talk to him about his joints. I wanted to…talk.

Every time he tried to speak, I was frustrated because I didn’t want to hear anything else. I had little patience for any other topic, and it dawned on me in then that probably a lot of his relationships were starting to look that way. Far from being my dad, he had become my patient. Furthermore, I remembered what I had taught as a psych teacher about a stage in life that men in particular reach when they want their life to have counted for something, and they want to share their stories with the younger generations. To bestow their wisdom.

I began to sob as I realized that my dad had been trying to talk, trying to tell, trying to bestow, but no one was listening. The dad I loved so much, whose stories were at the very heart of my childhood, must have felt so unheard, because I had not been listening.

I resolved in that pathetic little bathroom stall to be nothing more than his daughter. Not a doctor or a nurse, not a teacher, nor an historian, a grown woman, or an independent anything. I resolved to sit in humility at my dad’s proverbial feet and just be his daughter and to listen when he spoke.

So I started to call him and practice listening.

It began with just listening to his political frustrations with whatever was going on currently. But soon, those frustrations led to stories about how it was in his younger day, his teen years, his childhood. While I initially started listening intentionally to serve my dad better and bring more peace to our relationship, I discovered that his stories fed my soul in ways I never anticipated. I learned that he had so many more incredible stories that I ever knew, and he had os many more to share with me as an adult than he had when I was a child. The Iowa farm house, the hot West Virginia summers. Beyond family lore - it was the stories that grew him, shaped him, and drove him over time. I started calling more frequently just to hear more.

In November, he drove me around his old neighborhood in Detroit and told me stories, like being a boy on a bicycle trying to impress a pretty girl by racing her father’s car to the next block. I was as exhausted from traveling, but it was one of the best days we’ve gotten to spend together.

We as a society have really lost our sense of honor and fear. Think about the last time you heard a mainstream pastor preach about the fear of God. Think about the last time one of them preached about that sticky fifth commandment that says in no uncertain terms to honor your parents.

Maybe we think that’s just for children. When we grow up, we get to make our own decisions about whether or not our parents are worthy of such deference. Surely God can see we’re more educated and informed. We have more struggles than our parents did. How could they have wisdom that we don’t already possess?

Maybe it’s the way our culture treats elders. We even set a specific age when we can retire them into an oblivion where they can choose to become full time grandparents, or maybe part time grandparents and part time gardeners. As if the end of a career is the end of meaningful contribution. Sadder is how many look forward to the days of playing golf or chasing warm weather instead of using these sage years to pour into the lives of others.

These are generalizations, I understand, but do you have a better explanation?

However, that honor shines in the Word as a God-given commission that children have to lift our parents up. And to parents, particularly fathers, He commissioned them to teach their children explicitly. “And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise” (Deuteronomy 6:6-7).

In other words, our fathers were made to tell stories, and we were made to listen.

But this is not age-depending, and I do not see any boundaries on age in the commandment either. In fact, Solomon was not a young man when he penned the words, “Hear, my son, your father's instruction, and forsake not your mother's teaching, for they are a graceful garland for your head and pendants for your neck” (Proverbs 1:8-9).

We need the stories, and we have a generation that needs to be heard. Instead, we live in this culture that listens to reply or listens to repost or listens to correct. It takes humility to sit and listen. That awful H-word we all hate. But I urge you to love it instead - to be slow to speak, slow to anger, and quick to listen.

Through this experience, I have learned to honor my parents by deferring to their wisdom and, yes, storytelling. My life has been abundantly blessed by this, as God promises when we do what is right (Psalm 84:11).

In August of 2020, I found myself in a highly stressful situation at work, where I lived as a boarding school dorm mother and teacher. But as much as I prayed to be delivered and for justice to come, the Lord’s will was for me to stay there. So I began looking for a way to get away and breathe, a place to be unmasked and far from everyone I saw both day and night.

Some of my dad’s most alluring stories were about his days fishing the Au Sable and Manistee Rivers in Grayling, Michigan. These were the stories I grew up with, knowing he had been a great fly fisherman. I’d heard his daily stories when he came off the river as a guide when I was still very young, and I’d heard many more about his adventures with my Uncle Ford, Skip and Gail Madsen, and Bob Summers - institutions for a moment in that backwoods haven for trout chasers.

I’d always known I wanted to try, and I became motivated by an even more urgent drive than just the stress of my work place - that if I wanted to pursue those stories to make them my own, I wanted to do it while my dad could still tell me more and to share that connection together.

At first, it began with frustrations of trying to find someone to teach me here in Western PA, and then it was the difficulties of learning how to tie all of the knots, stop tying wind knots, cast properly, and then roll cast properly when I realized that there’s nowhere to backcast in PA. Those early days had far more failures than successes, and my dad had a story for all of them.

Lost flies. Lost fish. Snagged on a log. Snagged in a tree. Snagged on my own jacket. Hooking my first steelhead and having absolutely no clue how to reel in a fish that size or with that kind of fight. “Dad, I’m losing more fish than I land.”

“It’s OK, Brit. That’s how you learn. Heck, you know how many fish I lost? I was so frustrated when I first started, but I let it drive me to do better. I went to my mentors and I let them teach me how to do it right.”

Even later, he told me, you will lose fish. “I had to pole the boat, cast the rod, guide my clients, smoke my cigarette, and drink my bloody Mary at the same time!”

I learned that he similarly threw himself into the sport the way I did. Uncle Ford, Skip, and Gail mentored him the way a friend mentored me. He learned to cut through the lies of fishing quickly. No, you don’t need Orvis anything. You can catch big fish on short, light rods. One top water fish is always better than the twenty you nymphed. Drug store nail clippers are a suitable alternative to $130 nippers. It’s not actually cheaper to tie your own flies.

The last year has been nonstop stories - his from 30 years ago, mine from 30 minutes ago - connecting us in a brand new way. I call him after the majority of my fishing trips. My mom has gotten so used to it that when I call on Saturday afternoons, she asks, “Are you just getting off the water? OK, I’ll put Dad on.” Or I’ll hear her pick up the phone and simply yell, “Jon, it’s for you! It’s your youngest!”

Last summer, I had an amazing opportunity to fish my dad’s home waters on those storied rivers - Au Sable and Manistee. My dad’s body was not up to going, but I stayed with my parents for about three weeks in total, and I fished seemingly round the clock. In what was already the most mystical place I had fished, I got to go back in time and walk in my father’s footsteps in those days that he, as a younger man, chased wild brown trout and wilder days. Some days I did really well, and some days I got bested. I tried and succeeded and failed. I would come back to my childhood home, to his office all decked out in fly fishing gear with the summer breeze coming through the screen door, and I would tell him how I did. He shared more stories of trials and successes and failures. Funny stories, heartfelt stories, stories with great advice. He showed me rods, flies, and maps. I showed him pictures of ridiculous baby trout with their squishy little bellies. I never wanted to leave.

In a 2021 mid-summer Instagram post, I wrote the following:

“Three and a half weeks home, and I’m still not quite ready to go. There’s a call of the heart to cast one more line, dip in the fresh water one more time, tie on one more streamer. I’ve fished the [Au Sable], Manistee, Pine, and Boardman Rivers, plus Mud Lake and Green Lake. I’ve caught [brown trout, brook trout, rainbow trout, sunfish, blue gills, and bass] on the fly. I got to fish with my dad and every one of my siblings. It’s been 30 degrees, and it’s been 90 degrees. I’ve waded in fast water and smooth water, in sand and gravel and rocks, and I’ve thrown line from the deck of a BassTracker and cast from the water along a warm sandy beach. Most of all, I learned a ton about equipment, conditions, weather effects, species, environments, flies, and habitats…It’s so hard not to stay and keep exploring the water here.”

I did go back for more at the end of the summer. In fact I had a pretty wild year in fly fishing in general. While I have spent most of my time learning in PA and the bulk of last summer exploring Northern Michigan, and I’ve since fished in Maryland, West Virginia, and Wyoming. I’ve euronymphed, blue lined, and hucked big streamers. Been on every kind of fresh water boat you can think of and fished more than 50 streams and 10 lakes, as well as witnessing the breathtaking craftsmanship of building bamboo, fiberglass, and carbon fly rods from scratch.

But I, like my dad, know that it’s not the fish, but the stories that matter the most. The bass I lost because I was laughing so hard with my older brother. My sister and I getting skunked in our first hex adventure. The random act of kindness when two guys tried to brighten my day by handing me a couple of Miller High Lifes as they passed me on the stream. Meeting up with my friend Trevor, falling in the Potomac over my waders, and needing a full wardrobe change within the first five minutes of our trip. Even just listening to the stories of two outstanding rod builders as they crafted a 3-weight bamboo rod from culm to cast near the banks of the Big Horn River. All these stories, they shape our hearts and experiences going forward.

As I travel and meet people, I’ve taken the lesson of listening with me, and I think that’s part of the reason I’ve been blessed to have so many opportunities like these. Whenever I go somewhere and meet people - particularly in that Baby Boomer age range - I try to be intentional about stopping to listen to their stories. Like the trucker in Thermopolis, Wyoming who told me about his first shotgun, which his father had rescued from the dump where he worked, and for which, at age nine, had completely rebuilt the stock in order to shoot it. He hunted with it for years and still had it in his late 60s. What an honor to hear that story. Or the woman in my women’s fishing club who found her dad’s old gear and decided to give it a try late in life.

People are hungry to share, and we’re in an age that we all desire to be heard amidst the chaos of technology and social media that are advancing at an exponential rate. That’s not going to get any better, and so we have to make these daily choices to slow down, cultivate the humility to lend an ear, ask questions that invite another person to share what’s on their heart, even if it’s just “How long have you been fishing this stream?” or “How did you start fly fishing?” Everyone has a story. Everyone has something to share that will enrich your life and fill your heart if you can take the time.

I think many of us Storied Outdoor lovers have grown up with a father or a father-figure who influenced us deeply by sharing their passions and stories with us, who have inspired us to chase adventure and grow our own stories. I hope you have some time this Father’s Day to reflect on those memories and how they have shaped you.

As for my dad, he’s currently on a grueling upward trajectory of repairing his body. It has not been an easy road, but we’re closer to days on the water together than we have been in a long time. I know our mutual storytelling about a life on water has become an additional motivation for him to face certain mountains he’s now climbing.1

While he was in the hospital recently, he took on the role of the listener and began to glean stories from the staff and other patients around him. He tearfully told me how God had orchestrated the complications he was facing to encounter these people, and how he was grateful for his own suffering knowing that.

And he was faithful to share the most important story that any of us could ever tell–the story of the God Who loves us enough to die for us, Who wants our repentance more than our works or good ideas, Who hears our every word, and Who is woven into our every story.

You know, friends, your stories are so important. God gives us each a testimony to share, and there are times of hardship that may seem like that story isn’t a very good one. But everything He does and allows has great purpose. He made you on purpose, with great purpose, and for great purpose. So I hope two things for anyone who reads this:.

I hope you have the humility, curiosity, and discernment to invite others to share their stories with you.

I hope you have the humility, courage, and discernment to share your own.

Happy Father’s Day, Dad! For the record, Mom told what you said to the barber about me, and you’ve got me wrapped, too. I love you so much. Thank you for being my dad and sharing your stories with me. Keep them coming!

You know, as we reflect on this weekend’s events - stories of devastating floods in Wheeling, protests and celebrations across the nation, political murders in Minneapolis, and even the observance of Father’s Day in our own homes, it is now more important than ever that we make a concerted effort to listen to each other’s stories, and to share the most important story of all: that God became man and dwelled among us and died for the forgiveness of our sins, that we would have eternal life with Him. Let not the airwaves drown out our neighbors, as we continually live in community and let the world know us just as Jesus said it would - by the way we love each other (John 13:35).

Until next time, friends, may all that God created testify to His wisdom and power and divine nature, that you may be encouraged by His love all around you.

Unbeknownst to our family at this time, my father was in early stages of bulbar-onset ALS, and he would pass away within the year. It was a hard, harrowing, beautiful, and horrible year. I am certain that we will fish again in Heaven, and the stories will be phenomenal.